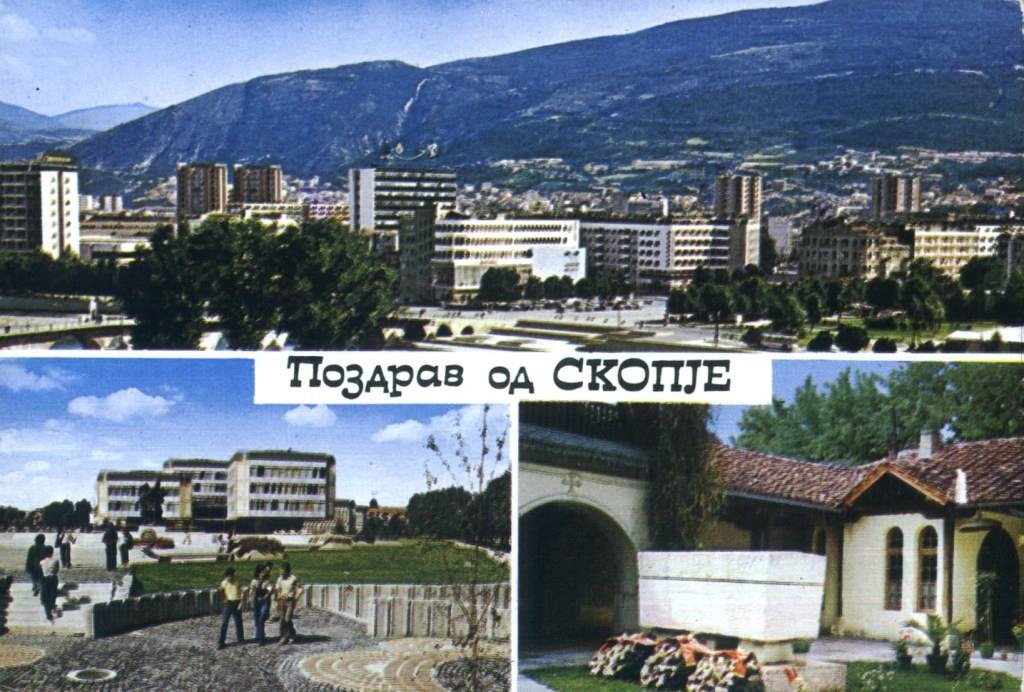

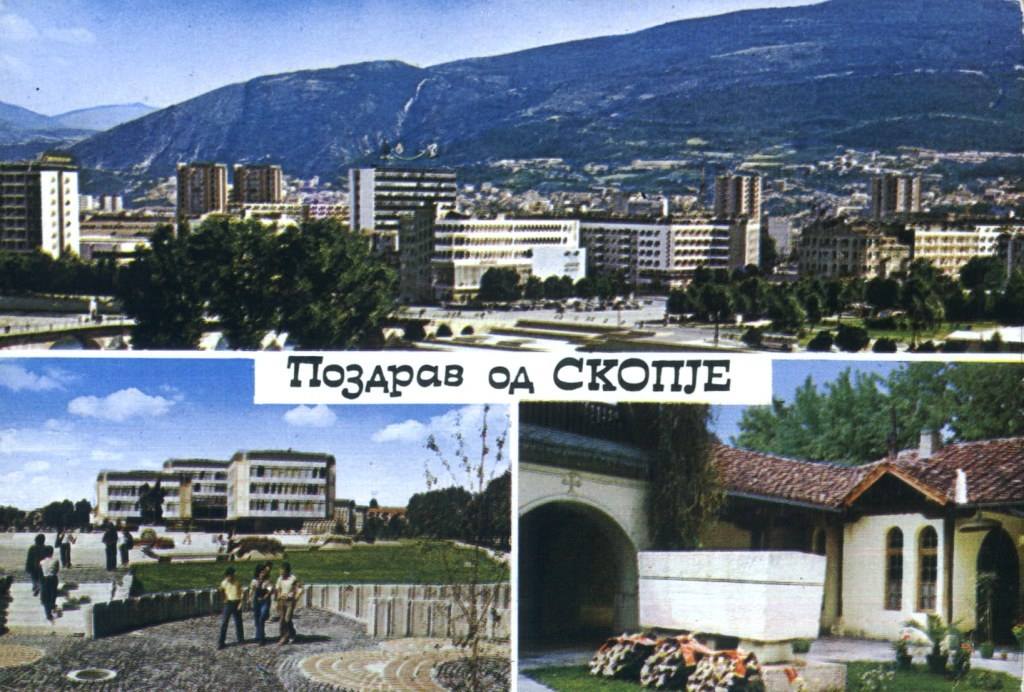

Lidija Dimkovska was born in 1971 in Skopje, Macedonia. She is a poet, novelist, essayist, researcher, and translator. She studied Comparative Literature at the University of Skopje and took Ph.D. degree in Romanian literature at University of Bucharest, Romania. Between 1997 and 2001 she worked as a lecturer of Macedonian language and literature at the Faculty of Foreign languages and literatures, University of Bucharest, Romania. Between 2009 and 2013 she taught World Literature at the Faculty of Humanistic at the University of Nova Gorica, Slovenia. In 2005 she got a research fellowship by Slovenian Science and Education Foundation Ad future to collaborate with the Institute of Slovenian Migration, Slovenian Academy of Science and Arts, on the project “Immigrant Literature in Slovenia”. Since 2001 she lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia as a free-lance writer and translator of Romanian and Slovenian literature in Macedonian.

Published books of poetry: “The Offspring of the East” (1992, together with Boris Cavkoski, which won the literary award for best poetry debut book), “The Fire of Letters”(1994), “Bitten Nails”(1998), “ Nobel vs. Nobel” (2001, available also on-line, second issue 2002), “Meta-Hanging on Meta-Linden” (poetry collection translated in Romanian, published by Vinea, Bucharest, 2001, which won the literary award at the international poetry festival “Poesis” in Satu Mare, Romania), “Nobel vs. Nobel” (translated in Slovenian, published by Aleph, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004), “Do Not Awaken Them with Hammers” (poetry collection translated in English, published by Ugly Duckling Press, New York, U.S., 2006, “Ideal Weight” (selected poetry in Macedonian, edition “130 books of Macedonian literature,”2008), “pH Neutral for Life and Death”, 2009 (translated in Slovenian, published by Cankarjeva, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2012, shortlisted for the International poetry prize “European Poet of the Freedom”, Gdansk, Poland, 2016) ), »Decent Girl«( poetry collection translated in German, Edition Korrespondenzen, Vienna, Austria, shortlisted for the German literary prize »Brucke Berlin«), “pH Neutral History” (poetry collection translated in English, Copper Canyon Press, the USA, 2012 shortlisted for 2013 Best Translated Book Award. In 2009, she received the European literary prize for poetry »Hubert Burda« , in 2012 the International poetry prize “Tudor Arghezi” in Romania and in 2016 the European Prize for Poetry Petru Krdu in Serbia. In 2016 she published her new book of poetry in Macedonian “In Black and White”.

In 2004 her first novel, Hidden Camera, won the award of Writers’ Union of Macedonia for the best prose book of the year. It has been translated in Slovenian (Cankarjeva, Ljubljana, 2006), Slovakian (Kalligram, Bratislava, 2007), Polish (PIW, Warszawa, 2010), Bulgarian (Balkani, Sofia, 2010) and Serbian (2016). In 2017 Hidden Camera is going to be published in Latvian and Croatian.

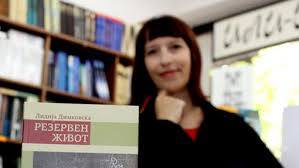

In 2012 her second novel A Spare Life won for the second time the award of Writers’ Association of Macedonia for the best prose book of the year. In 2013 it won the European Union Award for Literature. A Spare Life so far had three editions in Macedonian and in 2015 was the best read book in the main Skopje Library. It has been translated in Hungarian, (Napkut, Budapest, 2014), Serbian (Agora, Novi Sad, 2015), Bulgarian, (Colibri, Sofia, 2015), English (2016, Two Lines Press, San Francisco, a three-weeks literary tour in the States in October 2016), Croatian (2016, Ljevak, Zagreb), Czech (2016, Vetrne Mlyny, Brno), Italian (January 2017, Atmosphere Libri, Roma) and in 2017 is planned to be translated in Arabic (IBN ROSHD, Cairo), Latvian (Mansards, Riga), and Ukrainian (Books XXI, Kiev).

In 2016 she published her third novel “No-Ui”, shortlisted for the Novel of the Year Award of the Macedonian newspaper Utrinski vesnik for 2017.

She edited an anthology of young Macedonian poetry (Prokultura, Skopje, 2000), an anthology of contemporary Slovenian poetry in Macedonian (edition of the International poetry festival Struga Poetry Evenings, Macedonia, 2012, and an anthology of contemporary minority and immigrant writing in Slovenia, Slovenian Writers Association, Ljubljana, 2014, two editions.

She has participated in numerous international literary festivals, readings and book fairs (Berlin, Rotterdam, Stockholm, Vilnius, Chicago, Zagreb, Medellin, Leipzig, Sofia, Frankfurt, Goteborg, Vilenica, Medana, Struga, Sarajevo, Leipzig, Lido Adriano, Manchester, Taipei, etc.) and was a writer-in-residence in Iowa (International Writing Program), Berlin (LCB), Graz (IHAG, Rondo), Krems (Top22), Vienna (KulturKontakt), Salzburg (H.C. Artmann), Split (Kurs), and London.

Лидија Димковска

Од поетската збирка pH неутрална за животот и смртта, Блесок, Скопје, 2009.

Lidija Dimkovska

From the poetry collection pH Neutral History, Copper Canyon Press, USA, 2012 (shortlisted for The Best Translated Book Award 2013), translated from Macedonian by Ljubica Arsovska and Peggy Reid

Помнење

Помнењето ми е војничка конзерва паштета

со неограничен рок на траење. Се враќам на места

кај што сум стапнала со само еден јазик во устата

и на домородците им матам жолчки за добар глас,

во снегот од белки Исус лежи распнат како да се шегува,

за француски бакнеж се потребни два јазика,

сега кога имам неколку, не сум повеќе жена туку ламја.

Ни јас како Свети Ѓорѓи никогаш не научив

да пружам вештачко дишење, носот ми е затнат со години,

и сама дишам низ туѓи ноздри, светот плаќа.

Аха, не ти е чиста работата, не ти е чиста работата!

викаат зад мене паднатите ангелчиња

што собираат стара хартија и пластика,

најмногу ги сакам кога во ходникот ги изнесуваат

своите креветчиња да се проветрат од ДНК,

тогаш на нив се спружуваме со А. секој од едната страна

и во точно замислена љубовна прегратка

ни се поткршуваат сите порцелански заби,

непцата ни се претвораат во ококорени очи,

пред нив јазиците во темнината си ставаат сопки,

’ржат, цимолат и јачат, а нам не ни е ни страв ни жал.

Помнењето ми е црна кутија од паднат воен авион

со неограничен рок на тајност. Се враќам на места

кај што сум стапнала со само една крв под кожата,

на домородците им ги прецртувам плодните денови

во календарчето за имендени и домашни слави,

домашните животни копнеат по диви, дивите по питоми.

Како еврејски пар во денови на пост и месечни циклуси,

така и јас и Бог со години спиеме во раздвоени кревети.

Memory

My memory is a soldier’s tin of bully beef

with no best-before date. I return to places

I have trodden with only one tongue in my mouth

and beat egg yolks for the natives to give them a good voice.

In the snow of the whites Jesus lies crucified as if in jest.

It takes two tongues for a French kiss,

now that I have several I’m no longer a woman but a dragon.

Like Saint George, I never learned

to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation; my nose being blocked for years

I myself only breathe through others’ nostrils, the world is paying.

Aha! There’s something fishy about you, something’s fishy here,

the little fallen angels

collecting old paper and plastic cry after me.

I love them best when they take their cots

out into the corridor to air the DNA away,

then A. and I sprawl out on them, a side each,

and in a carefully worked-out act of love

all our porcelain teeth chip off,

our gums turn into wide-open eyes, before which

our tongues in the darkness trip each other up,

growling, whimpering and moaning, and we

feel neither fear nor sorrow.

My memory is the black box from a crashed warplane

with no sell-by date. I return to places I trod

with only one blood under my skin,

I cross off fertile days for the natives on the calendars

with their name days and family feasts,

tame animals long for the wild, the wild for the tame.

Like a Jewish couple during fasts and monthly periods,

so God and I have been sleeping in separate beds for years.

Бонсаи

Смртта ги ужаснува роднините во странство.

Треба да се фати авион, да се проголта колачето со ореви

што предизвикува афти, да се изгори јазикот од кафето

и во недостиг на проштално писмо да се прочита Life или The Economist.

Во недела не постојат статии за рубриката Култура.

Само статии за уредување на домот, на градината, на рајот.

Телеграмата што ја пратив патува со мене,

но во бизнис-класа. Поштенскиот службеник трипати ги преброја зборовите

како да се изумрен животински вид. Како јазик што може да се сочува

и со две жени што не се познаваат, а озборуваат ист маж.

Од страната на мајка ми има такви жени. Мажот умрел вчера.

И столови во домот има на кои никогаш не сум седнала,

со тврди седала резервирани за домашните светители

што се враќаат дома само за погреби и свадби.

Отсега моштите ќе си ги подаруваме и за годишнини

од полисата за осигурување за штета настаната со смрт.

Живите го наплаќаат секое умирање. Со пакетче хартиени марамчиња,

со нови црни доколенки, со оглас на плазма телевизор.

По погребот лежам под дрвото на животот

како бонсаи што чека со него да си играат децата на мртовецот.

Ми треперат жилките, корените ми се вслушуваат

во мртвите што гргорат како проточни бојлерчиња

и прскаат жешка вода во мојата капка роса.

Колку сè беше полесно со смртта во рацете на Бога,

кога ноќе ја сушев со фен реката под прозорецот,

кога војникот ми купи пуканки во зајачка капа.

А сега дури имам и хоби: одам на комеморативни седници

за непознати. На враќање стомакот ми се дуе од газирани пијалаци.

Од напишани говори проред 2,0 за загубата што нè снајде

сега и овде. Ќе го следиме неговиот пат.

Пијам крв од крводарители и веќе ми е полесно. Пробај и ти.

Во системско ливче за лото распореди си го животот

и не поништувај повеќе од седум бројки. Зашто и тебе

те скокоткале кога си бил бебе:

„Ќе те изедам, ќе те изедам…“ Љубовта е природна состојба

на канибалите. Останатите се излежуваат на кожени двоседи

и се обложуваат во петте минути Исусова слава.

Ќе се роди ли, ќе умре ли или ќе воскресне?

На електронската пошта на мртовецот

и понатаму ќе пристигаат понуди

„Изгубете 5 kg за 7 дена, гратис“.

И ќе се смалува дрвото на животот, ќе се ништи месото

околу коските дури не ги поништи

петте дневни оброци, дури не стане бонсаи.

Единствена граница помеѓу таму и овде е авионското прозорче.

Таму сум дрво за дрвна индустрија, овде сум дрвце за медитација.

Животот како и обично си подигрува со роднините во странство.

Треба да се издржи летот, да се купат travel fit парфемчиња,

да се затвори човек во тоалетот и долго, долго да мокри,

сè дури долу, врз гробот, мојот бонсаи не стане дрво со сенка,

а потоа во недостиг на тестамент да се прочита Financial или Sunday Times.

Во недела не постојат статии за рубриката Живот.

Само статии за уредување на потсвеста, на егото, на пеколот.

Bonsai

Death horrifies the relatives abroad.

There’s a plane to be caught, a walnut cake that’ll give me ulcers

to be swallowed, a tongue to be burned with hot coffee,

and for lack of a farewell letter Life or the The Economist to be read.

There are no articles for a section headed Culture in the Sundays.

Just articles on how to arrange your house, garden, paradise.

The telegram I sent travels with me,

but in business class. The man in the post office counted the words three times

as though they were an extinct species. Like a language that can be preserved

when there are just two women who don’t know each other but gossip about the same man.

There are such women on my mother’s side. The husband died yesterday.

And there are chairs at home I’ve never sat on,

with hard seats, reserved for the domestic saints

who come home only for funerals and weddings.

From now on we’ll be giving each other relics as presents

on the anniversaries of the insurance policy

against damage caused by death.

The living charge for each death. With a small packet of paper handkerchiefs,

with new black knee-length stockings, with announcements on the LCD TV screen.

After the funeral I lie under the tree of life

like a bonsai waiting for the children of the dead one to play with it.

My veins shiver, my roots strain to hear the dead

who gurgle like little water heaters

and sprinkle hot water into my drop of dew.

It was so much easier when death was in God’s hands,

when at nighttime I dried the river under the window with a hair dryer,

when the soldier bought me a carton of popcorn.

And now I even have a hobby: I go to commemoration services

for people I don’t know. On the way back my stomach swells with all the fizzy drinks.

With speeches written double-spaced on the loss that’s befallen us

here and now. We shall follow in his steps.

I drink blood-donors’ blood and already I feel better. You should try it.

Put your life in order with the lottery ticket

and never cross out more than seven numbers. Because you too

have been tickled as a baby:

“I’ll eat you up, I’ll eat you up…” Love is the natural state

of cannibals. The others lie around on leather sofas

and bet on the last five minutes of Jesus’s glory.

Will he be born, will he die, or be resurrected?

Messages will keep coming on the dead one’s e-mail

offers will keep piling up,

“Lose 5 kilos in 7 days, no charge.”

And the tree of life will keep shrinking, the meat will keep diminishing

around the bone until it vitiates

the five meals a day, until it becomes a bonsai.

The only border between there and here is the plane’s small window.

There I’m a tree for the timber industry, here I’m a little tree for meditation.

Life as usual mocks relatives abroad.

One must endure the flight, buy “travel fit” perfumes,

shut oneself up in the loo and pee for a long, long time,

until down there, on the grave, my bonsai becomes a tree with a shadow,

and then, in the absence of a will, read the Financial or the Sunday Times.

On Sundays there is no section headed Life.

Just articles on how to arrange your subconscious, your ego, your hell.

Разлика

Исусолози, Алахолози,

Цариград нема современици.

Овде сè е професионално,

тоалетната хартија, машината за перење,

лифтот, микрофонот, телесната маса.

Отаде совршенството умот е ограбен сеф

што крие само уште тага.

Живеам крај храм нафрлан со клима-уреди

како задоцнети сипаници кај старци.

На домофонот цел ден некој ме прашува

дали во зградата има свирач на хармоника.

Можеби знае чуварот на знамињата –

едното црно, разресено од домашните миленичиња

што се вее од балконите на самоубијците,

другото национално, избледено од перење

што се вее од прозорците на убијците.

Помеѓу раѓањето и смртта животот нема гаранција,

единствениот сервис за поправки е сè уште во нас самите.

Понекогаш горешто посакувам да сум воен инвалид,

да лежам врз бришалка за плажа со мотив на гола жена

пристигната од Шведска со Црвен крст.

Но, залудно, на ваков ден му е потребно целото мое тело,

а на ноќта само торзото. Независно со која рака се крстам,

четирите страни на светот

го промашуваат срцето.

Ќе го заштитам со апликација врз маицата,

со глава од Че Гевара или со веронаука:

Таоизам: Shit happens.

Будизам: It is only an ilussion of shit happening.

Ислам: If shit happens, it is the will of Allah.

Јеховини сведоци: Knock, knock: Shit happens.

Христијанство: Love your shit as yourself.

Само една песна знам да свирам на хармоника,

но и таа е римејк на историјата.

Брисот од мојот болен зајак го пратив во Виена,

а од болниот светител – во Рим.

Како и Ингебор Бахман, секој резервен дел

се враќа дома во туѓо возило.

Постоење издолжено во мртовечка кола

кому живите отаде стаклото

му симнуваат капа

и му мавтаат како кога се родил: Па-па.

Кога саканиот се врати од Цариград со жолтите дуњи,

Фатма од оној свет кисело му се насмевна.

Разликата помеѓу човека и Бога, мил мој, е само една:

Човек првин наоѓа, па губи.

Бог првин губи, па наоѓа.

Difference

Jesusologists, Allahologists,

Constantinople has no contemporaries.

Everything here is professional,

toilet paper, washing machine,

the lift, the mike, the body mass.

Behind the perfection, the mind is a safe broken open

that hides nothing now but grief.

I live by a temple blotched with air conditioners

like grown-ups with belated measles.

Someone is asking me all day over the intercom

if there’s an accordionist in the building.

The keeper of the flags might know—

one a black flag, tattered by domestic pets,

fluttering from suicides’ balconies,

the other the national flag, faded with all the washing,

fluttering from murderers’ windows.

Between birth and death life has no guarantee,

the only service station being the one still within ourselves.

Sometimes I burn with desire to be a war invalid,

to lie on a beach towel printed with a naked woman,

newly arrived from Sweden with the Red Cross.

But to no avail, for a day like this has need of my whole body,

and the night of my chest alone. No matter which hand I cross myself with,

the four sides of the world

miss the heart.

I’ll protect it with a print on my T-shirt

of Che Guevara’s head, or religious messages:

Taoism: Shit happens.

Buddhism: It’s only an illusion of shit happening.

Islam: If shit happens, it is the will of Allah.

Jehovah’s Witnesses: Knock, knock: Shit happens.

Christianity: Love your shit as yourself.

There’s only one tune I can play on the accordion,

and even that is a remake of history.

I’ve sent the swab from my sick rabbit to Vienna,

and that from the sick saint – to Rome.

Just like Ingeborg Bachmann, each spare part

comes home in someone else’s vehicle.

Existence lying supine in a hearse

that the living on the other side of the glass

take their hats off to

and wave as when he was born: Bye-bye.

When the beloved returned from Constantinople bearing the yellow quinces,

Fatima smiled at him sourly from the other world.

The difference between man and God, my darling, is just one:

Man first finds, then loses,

God first loses, then finds.

Национална душа

Откако брат ми се обеси со телефонскиот кабел

можам со него по телефон да зборувам со саати.

Копчето е постојано притиснато на Voice

за да му бидат слободни рацете, да може со нив

да лепи плакати врз божјите бандери

и да повикува на жолчна расправа на тема:

Дали е душата национална?

Од возбуда и двајцата се тресеме, истражуваме,

јас на овој, тој на оној свет.

Науката докажа дека руска душа на пр., повеќе нема,

дека оној кој сонува ангели, во смртта ги прегазува ко сенка.

Можеби постои турска, кркори во слушалката брат ми,

оти секое утро слуша црцор од чајникот на Назим Хикмет

пред да ја дотурка количката со ѓевречиња

до портите на земјата. Ќе ти купам едно за душа.

И потоа задишано молчи. И ја бараме македонската

врз регистарски таблички на божјопатот Исток-Запад,

во картонски кутии со натпис „Не отворај! Гени!“,

натоварени врз плеќи на проѕирни мртовци.

А на мртовците не можеш да се потпреш.

Мртовците се илегални имигранти,

со своите подуени органи продираат во туѓи земји,

низ отворите на своите длапки и со шилците на своите коски

си го копаат и последниот гроб.

Таму ја предизвикуваат и последната тепачка

за националните небеса

и за душата што повеќе не се поседува.

Сè поголем е бројот на луѓе без души, на души без имиња.

Во автобус не си стануваат, едни без други далеку заминуваат,

со посредници се бараат, но не се спојуваат.

Нациите си кршат јајца од глава.

Брат ми очајува. Јас станувам А.-национална.

Телефонскиот кабел што нè поврзува

ми се измолкнува од препотената рака,

го приклештува телефонот до ѕидот и се повлекува во штекерот.

Зошто никогаш за несреќните на оној свет

не се отвори бесплатна СОС линија?

Зошто никогаш не научив да запрам некого на пат кон смртта?

И јас како брат ми од раѓање барам влакно во јајцето,

откровение по секоја цена, разобличување на смислата.

А душите на луѓето што бараат влакно во јајцето

завршуваат на три начини: обесени со телефонски кабел,

во тела на поети, или и едното и другото.

National Soul

Since my brother hanged himself with the telephone wire

I can talk to him for hours on the phone.

It is set constantly at voice on

so that his hands are free to stick

posters on God’s poles

and call for a bitter debate on the subject:

Is the soul national?

Excitedly, we both tremble, do research,

me in this world, he in that.

Science has proved that the Russian soul, for example, is no more,

that in death those who dream of angels step on them as if they were shadows.

A Turkish soul might exist, my brother’s voice crackles into the receiver,

since he hears the chirrup of Nazim Hikmet’s kettle every morning

before he pushes the barrow of sesame rings

to the gates of Earth. I’ll buy you one in memory of my dead ones.

And then he lapses into gasping silence. And we look for the Macedonian soul

among the number-plates on God’s East-West highway

in cardboard boxes labeled “Do not open! Genes!”

loaded on the backs of the transparent dead.

But one cannot rely on the dead.

The dead are illegal immigrants,

their swollen organs penetrating other peoples’ lands,

with the jagged tips of their bones through their opening pits

they dig their final grave.

There they provoke their last fight too

for their national heavens

and for the soul that no one possesses any longer.

The number of the soulless grows, of the souls with no name to them.

They don’t offer each other a seat on the bus; the ones and the others travel far,

then they search for each other through agents but don’t meet up.

Nations throw insults at each other.

My brother despairs. I become A.-national.

The phone wire that connects us

slides out of my sweaty hand,

pinning the phone to the wall, retreating into the socket.

Why was no SOS line ever opened

for the unhappy ones in the other world?

Why did I never learn how to stop someone on the path to death?

I too, like my brother, have been splitting hairs since birth,

revelation at any price, unmask the meaning.

And the souls of those who split hairs

end up three ways: hanged with a telephone wire,

in the body of a poet, or both.

Назад повикана

Ме повика назад и морав да се вратам.

Со Peter Pan Bus од Њујорк до Амхерст

и 50 центи кусур вклештени во левата дланка

што на излегување, наместо во автоматот за кафе,

ги проврев во твоето минато за да ја отворам сегашноста.

А сегашноста е волк со распарана утроба

што преживеаните го полнат со камења,

зад него не останува ни капка крв,

ја ишмукале жртвите дури бревтале внатре,

оттаму е нивната жолчност

што посурово да го фрлат во реката.

И минатото го боли, но нема каде да се скрие,

а со тебе беше поинаку:

кога се скри во својата соба

ти се скри во своето време.

Среде куќата со лебови што никогаш не се стврднаа

соларникот беше бројченик на смртта,

низ ситните дупчиња пробиваа жилки на црни цвеќиња,

низ крупните – белилото на фустанот остро како зима,

а низ големиот отвор гргна ти самата:

„Is my Verse alive?“.

И потоа смртта стана почесна гостинка во домот,

со години излежувајќи се во бели чорапи среде црна постелнина

те демнеше да не го пречекориш прагот на татковата куќа.

Тебе ти е жив стихот, но не знам дали јас сум жива

дури повторно стојам во твојот двор во Амхерст

и читам оглас за изгонување зомби од тела на поетеси,

и се прашувам, замрзнува ли совеста на минус 7 степени,

и како да се стерилизира стерилизаторот

за да биде животот живот, а стихот стих.

Нашата средба е како петел заклан во чест на гостин од далеку

што се прпелка во сончевата тава на Амхерст,

секој невестински фустан се сеќава на твојот девствен,

секој букет фрлен одзади сака да се падне кај тебе.

А што остана? Соба – прв контејнер „Само за хартија“

што со години не знаеше дали заврши во депонија

или кај таен читател во потстанарска соба.

За тебе направив сè што можев. Имам маж, ќерка,

четири очи, две земји и две небеса.

Двапати дојдов, но куќата ти беше заклучена.

Потоа отрчав на гробиштата кај што ноќе со Дера и Џим

седите врз оградата како на нишалка надземи.

Таму, десно од патеката со зелени стракчиња

гробовите на Дикинсонови

се наредени како аптекарски шишиња,

а само врз твоето шишенце стои налепница

„Назад повикана“.

Called Back

You called me back and I had to return.

On the Peter Pan bus from New York to Amherst

with fifty cents change clutched in my left hand

and on leaving I fed it not into a coffee machine

but into your past to open the present.

And the present is a wolf with its belly ripped open

and filled with stones by the survivors,

not a drop of blood remains from it,

the victims have sucked it up while gasping inside,

hence their bitterness

in throwing it so cruelly into the river.

And the past hurts it, but it has nowhere to hide,

while it was different for you:

when you hid in your room

you hid in your time.

In the house with loaves of bread that never went hard

the saltcellar was the dial of death,

roots of black flowers pushed through the smallest holes,

and through the larger ones the whiteness of a dress as sharp as winter,

and through the biggest you yourself poured out:

“Is my Verse alive?”

Then death became an honored guest in the home,

sprawled for years in white stockings in the midst of the black bed linen

lying in wait for you should you cross the threshold of your father’s house.

Your verse is alive, but I don’t know if I am alive

as I stand once more in your garden in Amherst

reading the ad about exorcising zombies from poetesses’ bodies

and wondering whether consciousness freezes at minus seven degrees

and how to sterilize the sterilizer

so that life will be life, and verse—verse.

Our meeting is like a rooster killed in honor of a guest from afar

writhing in the sunbaked dish of Amherst,

every bride’s dress remembers your virginal one,

every bride’s bouquet thrown over the shoulder wants to fall into your hands.

And what was left? A room—the first “Paper Only” dustbin,

uncertain for years as to whether it would end up in the dump

or with a secret reader in a rented room.

I did all I could for you. I have a husband, a daughter,

four eyes, two countries and two skies.

I came twice, but your house was locked.

So then I ran to the graveyard where at night you sit with Dara and Jim

on the fence, as if swinging above the earth.

There, to the right of the path strewn with blades of green grass

the Dickinson graves are lined up

like chemists’ bottles,

but only yours bears the label

“Called Back.”

Живи и мртви

Носот ме чеша секогаш кога стигнувам на гробишта.

Мртвите се конечно кротки, но не и оние

што ги носат нивните имиња. Наследниците

првин роват низ ковчежињата со тапии и суво цвеќе,

а потоа пијат вода со шеќер и ги отвораат прозорците.

Како тоа овие пари не важат повеќе?

На редачките им се служи кафе и антисептик за грло.

И десната рака ме чеша, но свеќите донесени од град

не знаат сами од себе да капат водорамно.

Во секоја куќа со баба едно дете на распуст

ги реставрира светителите од календарот со восочни капки,

во секоја куќа со дедо врз споменарот се оставаат лушпите од јајца.

Ниту еден маж од мојот народ не е пријавен на моја адреса.

Иако од мала одев во берберница на потстрижување

и на улица можев да замолам некој чичко за чешлетo од неговиот џеб

кога околу мене тетките отвораа сетови со четки за коса и огледалце.

Некои никогаш не фатија вошки, на други им ги избричија главите.

Во крштевката на отпадници свештеникот воведе белење на косата

пред да ја потсече. Неколку дена масовно праќавме средства

за самохраната мајка со пет болни деца од епилепсија,

но кога излезе да се заблагодари, не издржавме да викнеме

„Зарем собиравме пари ти да си ја боиш косата?“

Децата имаа истовремен напад, клоцаа околу мајката со Wella 05

во забавено движење. На хип-хоп забавите од чешмите тече

само жешка вода. Морав да го испијам хидрогенот. Да ги исплакнам

мртвите кои треба да се бодрат како првоодделенчиња во септември:

„Цел живот е пред тебе за да научиш сè што треба“.

Цел живот. Во смртта времето е ќесе со спортска опрема за час по фискултура.

И наскоро ќе нема дете без маичка Keep Dry и патики Keep Fast.

И наскоро ќе нема мртовец што нема да биде мој.

The Living and the Dead

My nose always itches when I get to the graveyard.

The dead are docile at last, but not those

who bear their names. The heirs will first

rummage through the boxes with the deeds and dried flowers,

and only then drink sugared water and open the windows.

How come this money’s no longer valid?

The wailers are served throat pastilles with their coffee.

My right arm itches too, but the candles brought from town

won’t burn unless we cradle them.

In every house with a grandmother a child on holiday

restores the calendar saints with drops of wax;

in every house with a grandfather

eggshells are placed on the family album.

Not one man of my people is registered at my address.

Even though in childhood I had my hair cut at the barber’s

and could ask any man in the street for the comb in his pocket

when all around me aunties were opening their sets of combs and mirrors.

Some never caught lice, others had their heads shaved.

The priest has introduced bleaching of the hair of prodigal sons,

before he cuts off a lock at their baptism. For a few days we all sent money

to the single mother with five epileptic kids,

but when she came out to thank us we couldn’t but cry out:

“Were we collecting for you to dye your hair?”

The children all had a fit at the same time, kicking in slow motion

around their mother with Wella Flame Red on her hair. There was only hot tap water

at the hip-hop parties. I had to drink the hydrogen peroxide. To rinse out

the dead, who need a boost like beginners on their first school day:

“You have a lifetime to learn all you need to know.”

A lifetime. In death, time is a bag with sports gear for gym.

And soon there will not be a single child without a Keep Dry T-shirt and Keep Fast sneakers.

And soon there will not be a single corpse that won’t be mine.

Зрелост

Како можеше громот пред да удри во копривата

да го замагли засекогаш огледалото во бањата?

Толку доверба во термометарот зад вратата,

толку сомнеж во националната телевизија,

а кога бојлерот се распрсна на парченца

водоводџијата беше на народна прослава,

во едниот звучник кркореа цревата на водителката

во другиот огнометот предизвика јо-јо ефект,

кога се вратија дома бремените жени не ги собираше повеќе

ниту една туш–кабина. Поплавата е зрелост на сушата

како што е смртта зрелост на животот.

За да не потклекнам пред големата вода

ноќе си легнувам со штитници врз лактите и колената,

бојата на соништата зависи од размената на материи,

со бодликаво топче минувам по трагите на утрешниот ден.

Залудно ли свечено го положив забниот камен

за камен-темелник на музејската гардероба?

Во неа висат мантилчиња што ја пропуштаат Шекспировата бура.

Пред да станам А.-национална и јас елекот за спасување

го облекував преку глава, а сега преку кацига.

Телото ми е менувачница во Старата скопска чаршија,

пред неа без чадор стои мажиште со тетовирани мускули

што не ме пушта внатре да си побарам сметка

и со парите што ги менувам за починка без сништа

на духовните водачи им купува чевли од ѓаволска кожа.

Некои во нив богослужат, некои ги чуваат за на телевизија,

нозете на сите ни се мокри божем ни ги измила Марија Магдалена.

Во путирот и ова утро имаше само анемична плазма,

бебињата шмукаа прсти натопени со мирислива вода

за акумулатори и пегли, срцето на А. е те цреша во слатко,

те вишна во ракија. Кога не зборувам со себе повеќе од три часа

светот станува коктел на нишалка од бамбус среде наплатна плажа

и по неколку голтки морето не се гледа, морето не се гледа.

Ripeness

How could the lightning forever mist up the bathroom mirror

before it struck the one it was not supposed to?

So much trust in the thermometer behind the door,

so much suspicion of the national TV,

and when the boiler blew up in bits

the plumber was at a public celebration,

the presenter’s stomach rumbled through one of the loudspeakers

and the fireworks caused a yo-yo effect in the other,

and when the pregnant women got back home

they could no longer fit into any shower cabinet.

Flood is the ripeness of drought

as death is the ripeness of life.

At night I go to bed with pads on my knees and elbows

lest I give in to the sweeping waters,

the color of dreams depends on the exchange of matter,

I stroke the traces of tomorrow with a spiky ball.

Was it in vain that I ceremonially laid my dental plaque

as the foundation stone of the museum cloakroom?

Hanging in it are the little coats that let Shakespeare’s tempest through.

Before becoming A.-national I too used to pull on my life vest

over my head, but now I do it over my crash helmet.

My body is an exchange office in the Skopje Old Bazaar,

in front of it a heavy man with tattooed muscles and no umbrella

who won’t let me in to get a receipt,

and with the money I exchange with him for a dreamless sleep

buys the spiritual leaders shoes made of devil’s skin.

Some hold their Masses in them, others save them for appearances on TV,

we all have wet feet as if Mary Magdalene had washed them for us.

This morning again the chalice held only anemic plasma,

the babies sucked fingers dipped in distilled water

for batteries and irons, A.’s heart is now a cherry in jam,

now a morello in brandy. When I don’t talk to myself for more than three hours,

the world becomes a cocktail on a bamboo rocker in the middle of a paying beach,

and after a few sips the sea cannot be seen, the sea cannot be seen.

Идеална тежина

Средната класа е боди-арт на семеен излет:

си ги посипува влакната од телото и од ќебето

со железни струганки

и со магнетна плочка во лежечки став

си ги корне за последен пат. Во чистилиштето

нема контејнери за био-смет. Остави ми ги органите

да ми бидат мирисливи сунѓерчиња и облоги за глава

додека шлапкам во реката со солна киселина.

На брегот интелектуалците скандираат: Design or die!

но залудно – Бог крај човек што не го повикувал од дете

е како нож крај чинија со шпагети. Носи лигавче наместо костим за капење.

Москва има месечен циклус, Филаделфија еднослојна тоалетна хартија.

Знаеш и сам, во мигови на историски одлуки пука најкревкото

во животот на човека: кујнската штица.

И тогаш жилетот се одвојува од бричот, а синот од Богородица.

Кога влегуваш во собата со раскрвавен образ знам дека во огледалото

си го видел ликот на детето што сега е тешко 370 g и долго 21 cm.

Како една поли салама, велиш, и потоа заспиваме на нозе.

Во нашиот замрзнувач грчи во зимски сон мечката од зоолошката.

Ноќе си ладиш пијалак меѓу нејзините колена,

а јас меѓу моите стискам радио на долга бранова должина,

како тула што се лади или термофор што пропушта,

реалноста се лулка во застарени вести, секоја ноќ станувам сè поводоотпорна.

Нашата река се гледа само од прозорчето на визбата.

И никој повеќе не умира до крај. Средната класа гребе цени од подароци,

кити прозорци со ласерски ѕвезди, во гумени ракавици

си игра театар со сенки. Ти се плази додека викаш:

„Професионално изгонувам зомби! Бидете повторно слободни!“,

а знам, ако си предебел или преслаб и животот и смртта се исто бреме.

Крстот исправено може да го носи само човек со идеална тежина.

Ideal Weight

The middle class is body art on a family outing:

sprinkling their body and blanket hairs

with iron filings and lying there

depilating them with a magnet for the last time.

There are no biogarbage bins in purgatory. Leave me

your organs to be my aromatic sponges and compresses for my head

as I wade through the river of hydrochloric acid.

On the bank the intellectuals chant: “Design or die!”

but in vain—God at the side of a man who hasn’t called on him since childhood

is like a knife at the side of a plate of spaghetti. He wears a bib

instead of a bathing costume.

Moscow’s got her period, Philadelphia is one-ply toilet paper.

You know it yourself: in moments of historic decision

what is most fragile in one’s life will crack: the kitchen chopping board.

It is then that the blade breaks from the razor,

and the Son from the Holy Mother.

When you enter the room, your cheek bleeding, I know you’ve seen in the mirror

the face of the baby that now weighs 370 g and is 21 cm long.

Like Poly salami, you say, and then we fall asleep on our feet.

The bear from the zoo snores hibernating in our freezer.

At night you cool your drink between its knees,

and between mine I squeeze the radio, tuned to longwave:

like a brick that’s cooling down or a leaking hot-water bottle,

reality rocks in out-of-date news, every night I become ever more water-resistant.

Our river can be seen only through a small basement window.

And nobody dies absolutely anymore. The middle class scrapes

the price tags off presents, decorates windows with laser stars, plays shadow theater

with rubber gloves on. It makes faces at you as you cry:

“I exorcise zombies professionally! Be free again!”

and I know if you’re too fat or too thin life and death are one and the same burden.

Only someone of ideal weight can carry the cross upright.

Клуч

Кога клучот ти висеше околу вратот

главата ти беше стомаче на Буда

што го галеа роднини претприемачи

со непроменлива новогодишна желба

(пари = здравје, среќа и љубов),

тие имаа омилен сон, ти омилен кошмар,

Бах на радио, грав во чинијата и Бруно Шулц

во став мирно во туш-кабината.

Среќниот човек се полни надвор, а се празни дома

(џебови, желудник, ум, сперма),

само празнината се остава врз анатомска перница

што ти ја помни главата

и кога клучот одамна ја изгубил врвката.

А сега, кога и несреќата е полнење

стомачето на Буда треба да се истрие од навлаката на перницата

или да се смени со некое поново божество,

менувањето на постелнината ја менува и среќата

како батерија во полнач што престанал да трепка.

За сè ти е потребен клуч освен за совеста

хортикултурно уредена со англиска трева, џуџе и сензорска ограда,

дом во којшто едниот, единствен бог е патронажна сестра

што доаѓа во посета три дена по раѓањето и три дена пред умирањето.

Во црното куферче со клуче со два запца

еднаш носи вага за животот, другпат вага за смртта.

Key

When the key hung around your neck

your head was Buddha’s tummy,

rubbed by relatives and entrepreneurs

with an unchanging New Year’s wish

(money = health, happiness, and love),

they had their pet dream, you had your pet nightmare,

Bach on the radio, beans in the bowl, and Bruno Schulz

standing to attention in the shower cabinet.

A happy man gets charged up outside, and emptied at home

(pockets, stomach, brain, and sperm),

only the emptiness is left on the anatomical pillow

that remembers your head

even when the key has long since lost its string.

And now, when unhappiness too is a charging,

Buddha’s tummy needs to be rubbed against the pillowcase

or be replaced by some newer deity,

changing the bed linen changes fortune too,

like a battery charger that no longer blinks.

You need a key for everything but your conscience

horticulturally arranged with an English lawn, a garden gnome, and a sensor fence,

a home where the one and only god is the community nurse

who comes to visit three days after the birth and three days before death.

In her black bag locked with a two-pronged key

once she carries scales to weigh life, the next time to weigh death.

Books by Lidija

Pictures from Macedonia