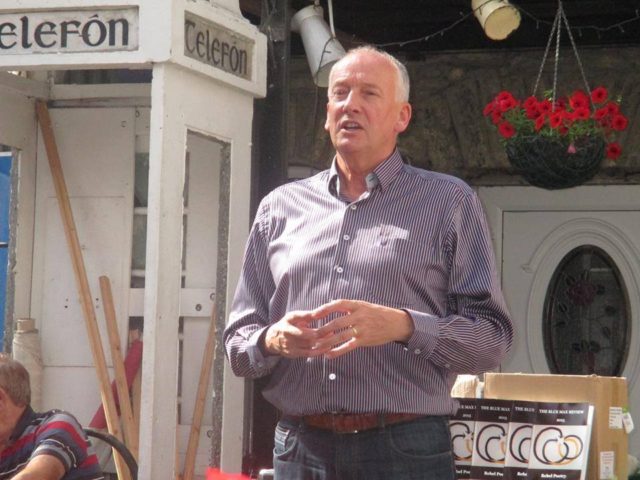

Biography

Gene Barry is an Irish Poet, Art Therapist and a practicing Psychotherapist. He has been published widely both at home and internationally and his poems have been translated into Arabic, Irish and Italian.

Barry is founder of the Blackwater Poetry group and administers the world famous Blackwater Poetry Group on Facebook. He is also a publisher and editor with the publishing house Rebel Poetry. Barry is also founder and chairman of the Blackwater International Poetry Festival.

As an art therapist using the medium of poetry, Gene has worked in hospitals, primary and secondary schools, NA, Youthreach, retired people’s groups, AA, asylum seekers and with numerous poetry groups.

Gene has read in Australia, the US, the Caribbean, Holland, England, Scotland, France and Belgium and as the guest poet at numerous Irish poetry venues.

In 2010 Gene was editor of the anthology Silent Voices, a collection of poems written by asylum seekers living in Ireland. Barry’s chapbook Stones in their Shoes was published 2008 and in 2013 his collection Unfinished Business was published by Doghouse Books. His his third collection called Working Days will be launched in September 2015.

Gene also edited the anthologies Remembering the Present in May 2012, the 2012, 2013 and 2014 editions The Blue Max Review and Inclusion as part of the Blackwater International Poetry Festival. In 2014 Barry edited Irish poet Michael Corrigan’s debut collection Deep Fried Unicorn, and fathers and what must be said and The Day the Mirror Called and MH Clay’s new collection sonoffred.

Heart,

come down from that loft, you’ll hurt yourself.

Green trains and old radios don’t walk away,

they lie beside posted forgottens and in movies,

tailor’s mannequins and framed paintings.

You’ll not find a squeaking pair of gates,

or a heavy-footed roaring engine clutch

screaming hide quickly, don’t be a crybaby.

That pool behind your tank has dried you fool,

and the worn beam that took four

of your finger nails is evidence-free.

Every known surprise you open contains

father’s deafness that kicked in when you

wore short pants and skin patches that

matched the purple jumper mother knitted.

The very same year his number 12s began

to kick little bodies and murder pets.

There are no replays correcting themselves

into heartbeats and happy mindsets.

Líne Iata

do na fir scartha

Shiúlainn go dtí crann mo chrochta

uair sa tseachtain agus chothaínn an téad

le súgán fear singil. Agus romham amach

teaghlaigh ag gliúcaíocht le drochmheas,

ceirteacha a gcuid maslaí á gcroitheadh

acu orm le gach dath faoin spéir.

Gan ghíocs gan ghuth dheintí é,

gan chor, gan chaint.

i ngan fhios don arraing péine a

chuir siad tríom. Go smior na smúsach.

Gamail gan rath amuigh leo féin

gan beann ar chúram clainne.

“Sinne” ina staic i ngach gairdín

nár linn, ag rince go fiata

i rith an lae sa ghaoith sin a

múchadh ina lios gan síóg.

Bogha ceatha a gcuid scéalta

ar ghob geabach a dteanga.

Níor dheineamarna na héadaí

a bheathú, ná an glantachán a

theasargan ón bpoll. Súile a

d’fhoghlaim teorainneacha na

cainte ón dtuiscint chúng a bhí acu

don teach, don teaghlach, don mhuintir.

Dhlúthaigh gach aon duine eile le chéile

lena ngáirí barbíciú, lena gcabaireacht

theolaí cois tine. Lasmuigh dár gcuid

clathacha lean siad orthu ag sméideadh

lena gcuid meirgí gan chrích

laistigh d’fhallaí a ndúnphort féin

Closed Line

For separated fathers

I would walk to my gallows

once weekly and feed the rope

with single men. And witness

the gawking families

unilaterally waving the many

colours of unity’s insults.

They would do it without

moving or speaking. Without

even knowing the pain they

had infused. Marrow bound.

A line of useless drones out

of sink with family matters.

“Us” was parked in every garden

that wasn’t ours, dancing all

day in wind that ceased to live

in what seemed to be the only

lifeless garden. Rainbows of

stories sticking out their tongues.

“We” never did the feeding of

the nylon, nor the retrieving

of the cleansed. Eyes set down

from conversations at both

boundaries that were lent to

what we now knew as a family.

Everybody beyond our ditches

seemed to gel with the laughter

of coal bunkers and barbeques,

to continue the unfinished over

the flapping icons that waved

them inside their castles.

A Different Heroin

One morning she saw no roads.

Street-fatigued,

she stepped off the tram

on Nieuwe Binnenweg,

a yellow cirrhosis painted canvas

at last giving that notice

she had always craved.

There was a gnawing

at the heels of her trodden wish list,

that same torment from her

equally tortured childhood.

So she stroked

the undergrowth of her ego

and stepped through

I.V. lines, blow jobs,

fibrillation and innocence

that had been climbing for

14 tormenting years

and whispered to herself;

bury me up to my conscience

in a wood with no name,

leave the headstone unetched.

.

In the Black

My mother’s breasts fed a nation.

Winning-bound greyhounds

fed from them on Saturday evenings

and on Sunday mornings a parish of

incapable men with hangovers

dangled from both nipples,

sipping and dreaming excuses.

They could finish difficult crosswords,

paint awkward skirting boards and

tell when lies were being delivered.

Cars found parking there.

There was no post code and yet

the messages of needs arrived

and were read and ciphered unopened.

One uneventful evening I pierced

a redundant corner, hand shaking

and lip quivering I tasted new fresh fruits

and expensive meat cooked perfectly.

Their built-in wardrobes oozed out

fashion pleasing little numbers to

perfectly fit and suit schoolfulls of

the ragged owned by sad mothers.

The day a few musical instruments

came in tow, I became a millionaire.

So I strummed till bed time came,

when she read to me the perfect children’s

books they had earlier written and printed;

somehow I always wished for a bicycle.

oman”,”serif”;background:white’>